One of the biggest problems I’ve had in solo-development, is just staying consistent. Just sitting down and doing the work on any sort of a consistent basis. Inspiration is something that comes and goes, and while ideally you’ll always be inspired and striking while the iron is hot, realistically that’s just not what happens. Inspiration ebbs and flows in anything creative but most noticeably so in anything long-form, which game development is for sure. It can takes weeks of work for even the smallest projects, and exponentially more for solo projects.

That’s not to say this is a problem unique to game development. I don’t think there’s a person alive who hasn’t struggled deeply at some point in their life to do something as simple as cleaning their room. To be, and to remain, consistent is something I always have and will continue to struggle with. And that’s okay. But there’s things I can do to help to fix it.

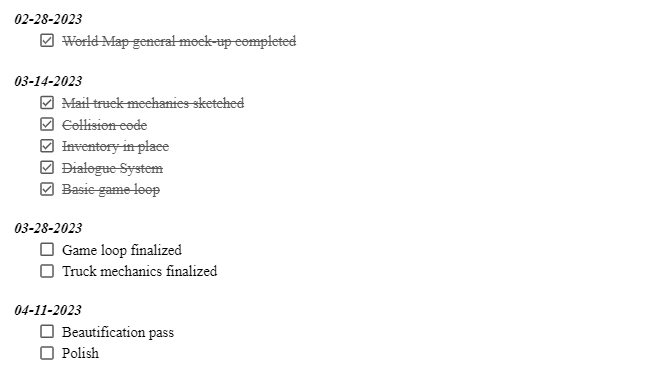

Notably, just breaking things down into smaller chunks has done wonders. That’s not exactly Earth-shattering advice, I know. I’ve heard that recommended time and time again. But there’s a reason people keeping saying it… it works. I implement this in game design starting at Day 0. Before I write a single line of code, or put a single pixel on a canvas, or write a single note of a piece music, I draw up a timeline of things that need to be done and estimates of how long they’ll realistically take. You can take as long as you need on this. Having a clear and concise plan-of-attack that breaks everything down into small, achievable goals is what I consider to be one of the most important things you can do in pre-production. Think of this timeline as living beside your Game Design Document (GDD). The GDD is what you want to make, and the timeline is how you’ll make it.

It can be as simple as a Word document listing things to do and when you hope to have them done by.

I typically like to have one larger timeline for the big pieces of the puzzle, and then a separate one for smaller ‘sub-goals’ inside each of the bigger ones. Taking the world map as an example. I decided very early on that the playable game space would consist of a 2000 pixel by 2000 pixel square. One of the first things I did was to block off where the different parts of the world would be. A town here, a field here, etc. But when the time came to actually go in and add various details, and really draw up the game space outside of the placeholder colored squares, the task seemed almost too monumental to even begin. So I broke up the world-space. Instead of doing multiple passes on a canvas 20002 pixels, I would work on a single 500×500 pixel grid, before moving on to the next. This took a task that at first seemed so daunting that I would want to put it off, and turned it into something more than manageable, and with very clear daily goals.

Now, 20 grid squares is still a lot of work. But what’s important is to try and forget about the bigger picture and just focus on what exactly I’m supposed to do right now, which is a lot harder to do if you don’t split the task up. Today I’ll draw grids A-1 and A-2. Tomorrow I’ll draw A-3. The actual workload hasn’t really changed, but by cutting it up into bite-sized pieces, you get a daily sense of accomplishment and most importantly you maintain your forward momentum. When you focus too much on the big picture stuff, it’s easy to get rapidly overwhelmed. And I think that overwhelming feeling is really where the root of inconsistent work is.

You want to maintain a string of little victories along the way until one day you look up and realize all those little victories have cascaded into one really big one.